Plato’s Allegory of the Cave: Variations on Liberation and Enlightenment

July 31, 2018

Recently in my work on Genesis 2 and 3, which I want to share some day, I was confronted with my inadequate understanding of Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” by an internationally acclaimed artist of Johannesburg, William Kentridge, who delivered the Norton Lectures of 2012, Six Drawing Lessons, at Harvard University in 2012. I realized that I had been transgressing one of my hermeneutical principles: “Always interpret a text in relation to its context.” But I would modify that, and I have frequently, in order to appropriate its immediate meaning for a purely subjective application.

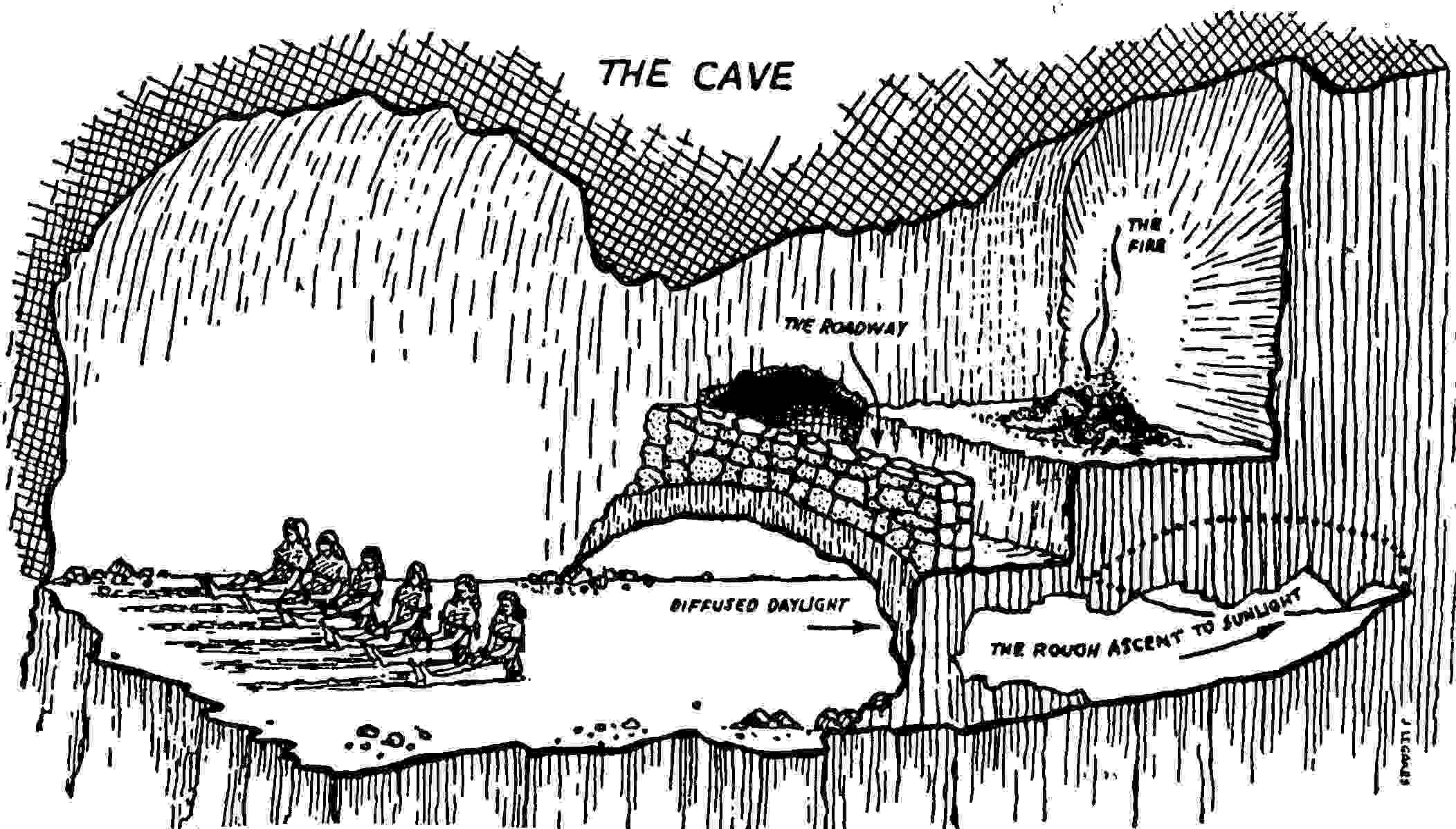

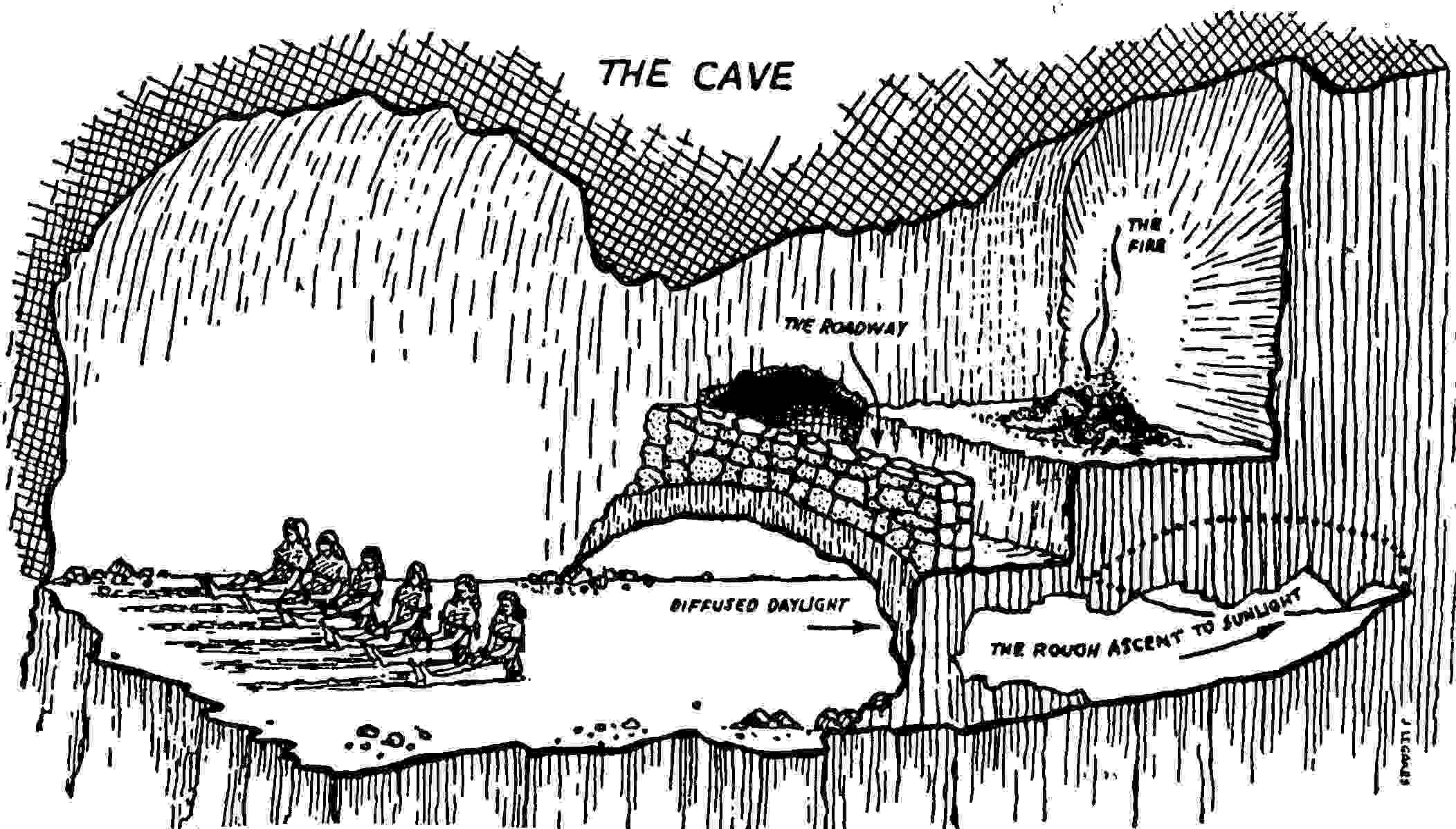

Of course, all of us are familiar with Plato’s Cave, and to one extent or another all of us may have usurped it for our own individual objectives. I suppose that we have no difficulty relating to it because we have imagined ourselves to have been in the cave, to have been released from the chains that held us in our seats and, by exiting from the cave, to have entered into the world of reality. Who would want to spend a life-time in the dark shadows of appearances and illusions? We may have been inspired to follow Plato in order to be liberated from the meaninglessness of the cave and to experience the gratification of our eyes gradually growing accustomed to the brilliant light of the sun so that we could contemplate the forms or universals of the Good, the Just and the Beautiful.

With this myth embedded in our psyche, we can easily identify ourselves with John Ashley of Thornton Wilder’s novel, The Eighth Day. He is a mining engineer of Coaltown, Illinois, who, like everyone else in that community, never experiences sunrises or sunsets because of its widespread pollution. Falsely charged with the murder of Breckenridge Lansing, he is put on a train to Springfield, Illinois to be executed, but he is rescued by strangers, put on a horse and instructed to find his way to New Orleans in order to escape from those who will be searching for him. He cheats at cards in order to buy passage to Chile where he resumes his profession and eventually encounters Maria Icaza who interprets his dreams and serves as his midwife for rebirth into a meaningful life of serving the needs of those who labor with him in deep caverns of the earth.

We happily join Will Barrett of Linwood, North Carolina, who, in Walker Percy’s novel, The Second Coming, is existentially driven to test the reality of God’s existence by entering a cave with a two week supply of water to prove to his satisfaction the truth of God’s being. He wants to be a believer. If he dies in the cave, it is unimportant because it can only mean that there is no God. Within a week he succumbs to a toothache, and when it becomes unbearable, he struggles to exit from the cave and stumbles into a greenhouse that has newly been occupied by Allie, a young woman recovering from a forced internment in a psychiatric hospital, and she nurses him into recovery. Reflection on the madness of his venture climaxes in a liturgy in which he cites all the forms of living death in our society and bellows, “Why this sadness here? Don’t stand for it! Get up! Leave! Go live in a cave until you’ve found the thief who is robbing you. But at least protest. Stop, thief! What is missing? God! Find him!”

As meaningful as these fictional representations of Plato’s cave may be, it is necessary to return to the allegory to reexamine it in relation to its literary context of The Republic and determine its function and application. Its objective is the education of “the best natures [of society]… to make the ascent, and view the good. They are to be the philosopher kings who will govern the community, “like leaders or kings in a hive of bees.” When they have seen all they need to see, they must return to the cave “to join the others in their dwelling place,” and use “persuasion and compulsion to bring its citizens into harmony.” As they lead them upwards to exit from the cave, they divide the people into classes and “make them share with the other classes the contribution they are able to bring to the community.”

Here is “enlightenment, liberation and violence.” It is the relation of knowledge to power! It is personified by Eve in Genesis 3 as she and Adam eat the fruit of the tree of the knowing good and evil, and, as the Hebrew Scriptures witness again and again, the tantalizing ambiguity of this knowing, generates more evil than good because the underlying motivation remains uncertain.

As fiction discloses, there are different modes of existentializing Plato’s cave. But to follow the all-seeing philosopher out of the cave and back into the cave is generally the procedure of those who inhabit the powers and the principalities of government, the so-called philosopher-kings, who claim to see while they denigrate and deny the seeing of those whom they have relegated to the darkness and illusions of the cave.

An oppositional variant of Plato’s Allegory is the culminating seventh sign of Jesus’ ministry in the Gospel according to John, the resurrection of the one whom Jesus loved, Lazarus. At his burial he is entombed in a cave, in Greek a spēlaion, and, through his sister, Martha, who has the stone rolled away because she “believes in order to see,” Jesus is able to call him out of the tomb, symbolic of both the death of living and the death of dying. Lazarus hears his bellowing call and responds, but his hands and his feet are constrained by burial bandages, and his eyes are covered by a face cloth. He is free, but he is not free, and the by-standers of the crowd are summoned to participate in his resurrection by liberating him from his grave clothes and enabling him to see the light of the first day of creation.

As Jesus’ disciples, we are not called to enter into caves of non-being to deliver its prisoners into the light of day. Rather, like Martha, we are charged to roll away the stones that are preventing those in the tombs of living death from exiting into the fullness of life. We do this because we do not separate ourselves from the many forms of living death around us. It may also be that we will encounter occasions in which we, on behalf of Jesus, must issue the call to someone in the tomb, “Come out!” And every day, like the observing bystanders, we encounter endless possibilities to show love and compassion to those who have exited from the tomb of living death by assisting them to take off their grave clothes. Resurrection into the fullness of life is God’s objective for all human beings, and we as the Community of God’s New Humanity are implicated in the profession of salvation. Like Jesus, we have added a new predicate to our identity, “I am the resurrection and the Life!”