By the time Rev. Stewart Perrilliat was in the fourth grade, he knew how to disassemble a machine gun and put it back together.

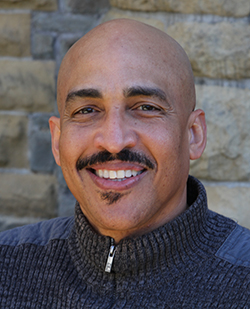

“I grew up in East Oakland when it was the murder capital in the early ‘80s,” says Perrilliat '16 (M.A.T.S.), and current Doctor of Ministry student at San Francisco Theological Seminary (SFTS) at the University of Redlands. “What I was being exposed to as a young person is what most people are never exposed to in a lifetime.”

Still, Perrilliat says he was fortunate. He was highly talented in basketball, and that earned enough respect that he didn’t feel he had to join a gang. Basketball was his gang.

Another young man was not so fortunate. Perrilliat met him during a basketball game and quickly learned that besides sharing his sports talent, the younger man was also from East Oakland and had even attended Perrilliat’s high school. But that is where the similarities ended.

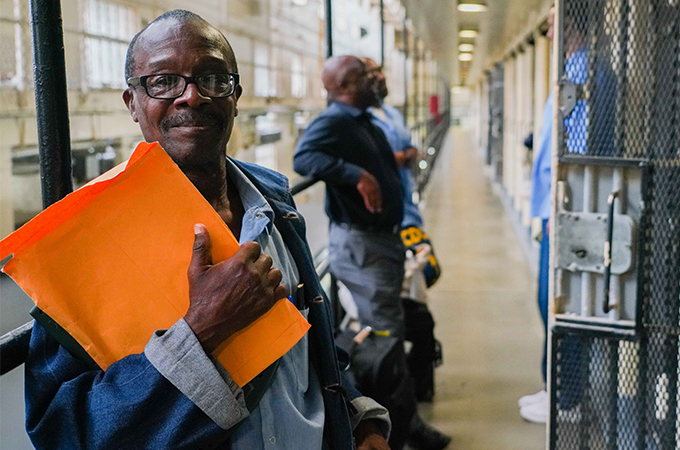

The basketball game during which Perrilliat met the young man took place in California’s San Quentin State Prison. Perrilliat was doing prison ministry, including some friendly games with prisoners, and the other man was an inmate. “He said he’d had a full scholarship to Morehouse College,” recalls Perrilliat. “During the summer, he thought he’d hustle to make some money before he went back to college. He got caught.” That was more than 20 years ago, and Perrilliat still ministers to inmates weekly.

Creating Man 2 Man

These experiences inspired him to create Man 2 Man - Urban Youth Advocate, a nonprofit organization designed to impart life skills, including anger management and conflict resolution, to young men of color. He is also an ordained minister, for whom Man 2 Man and his other service activities are important ways to live his faith outside the walls of the church.

“I have a passion to speak to these young men and share the word of God the way Jesus shared,” he explains. “I share my faith through stories—stories of the Bible, of my life, of friends who are no longer around.”

“I lost a lot of friends to crack, to selling drugs,” Perrilliat says. “When I share my stories with these young men, it resonates. I tell them, ‘You are who I used to be.’”

Man 2 Man holds classes and group mentoring sessions for young men referred through word of mouth and various organizations, or sometimes mandated through the courts for anger management. Perrilliat also produces a talk show, “Can We Have a Conversation?,” which airs on a local cable channel, and addresses issues of social and economic concern for people of color.

The talk show aims to give guests a platform to discuss issues and challenges they are facing in a safe, non-judgmental environment. “These young men feel hopeless and helpless, which is often expressed as anger, and, because of this anger, many of them act out in violence,” he comments. “That’s their way to communicate.”

One of his goals is to help young men become positive, involved fathers. Men of color who lack father figures have greater rates of incarceration, domestic violence, low self-esteem, drug addiction, alcoholism, teenage parenthood, and other issues, says Perrilliat, who is himself an involved single father of two children, ages 12 and 15.

Perrilliat remembers an encounter while working with boys incarcerated in juvenile hall, most of them 15 or 16 years old. He asked the group how many of them had children, and the majority raised their hands. Then he asked how they provided for children at their ages, and one replied that he took what he wanted.

“I asked him about this,” Perrilliat recalls. “I said to the man, ‘You take what you want? That’s how you provide for your family? You steal? I’m a single father and I go to work to take care of my children. So you’re going to steal from me and take what I worked for, to take care of your children?’”

“The guy said he never thought about it like that," says Perrilliat. "They don’t think, they just respond, because they’re in survival mode.”

Through its various programs, Man 2 Man endeavors to impart personal and communication skills to the young men who participate. “It taught me how to better manage myself and taught me that I have control over nobody but myself and my actions,” says a dreadlocked young man in a video testimonial Perrilliat recorded after one session.

The young man continues: “How to control things I do and better understand other people and not be so centered on myself… It’s made my relationships a lot better and made who I am a lot better person too.”

For Perrilliat, that’s what it’s all about.

'Maybe if I had a dad'

One young man in Man 2 Man is nonchalant at first, seeming to downplay the impact of his lack of a father. Friends’ dads were there for him, he says, along with other role models. But as he speaks more, another side of his story emerges.

“I went to juvie when I was 12 years old, selling drugs,” he shares. “Maybe if I had a dad to help me or show me that that wasn’t the way to go, you know … But I had nothing. I was wearing the same pair of pants. My dad could have bought me something …”

The men at this session were ordered by the courts to participate in Man 2 Man, which has served voluntary and mandated participants around the San Francisco Bay Area since 2007. Now, however, the program is vastly expanding its reach: This summer, Man 2 Man is launching an online course with 16 interactive sessions over eight weeks, as well as fledgling programs around the U.S. and internationally in Canada and Africa.

The model developed by Perrilliat is designed to create an environment conducive to reflection. “Men, I think, tend to be fairly introverted, we don’t talk about our feelings, but by the end of the sessions they really start to open up,” comments Matt Anderson, a filmmaker and friend of Perrilliat who has witnessed and filmed several sessions. “Stewart presents very practically and conversationally and transparently … guys can actually see other people similar to them open up and be honest about their pains and their failures and how they overcome those failures.”

Now Perrilliat is working with Anderson to make a documentary about fatherhood. For both, the topic is personal: Both have been single fathers, and they grew up together in the disadvantaged neighborhoods of Oakland, California, where they witnessed tragedies that Perrilliat attributes largely to fatherlessness. “We’ve lost a lot of friends, we’ve seen a lot of murders, a lot of people getting incarcerated,” he says. “And so we both have a passion for fatherhood.”

The duo has interviewed men ranging from prison inmates and former drug addicts to ministers, academics, and business leaders about their experiences with—or without— fathers, and as fathers themselves. These include Tracy Martin, father of slain Black teen Trayvon Martin; former NBA player and Hall of Fame member Gary Payton; writer and criminal justice reform activist Shaka Senghor; and Grammy-winning music producer and musician Narada Michael Walden, among many others.

Some tell powerful stories of how their fathers influenced their success; others share the opposite. At times, the raw emotion is overpowering. At one point, tears fill the eyes of a prison inmate as he stares offscreen. “What do you say to a son that you’ve abandoned for 20 years?” he asks. “What do you say?”

Some are stories of hope and redemption, like that of Assemblies of God Northern California and Nevada Assistant Superintendent Dr. Sam Huddleston, who got into trouble as a teenager after his mother left the family, and wound up in prison for second-degree murder. He got his life together, however, with his father’s support, a tale recounted in his autobiography. “His father never gave up on him,” says Anderson. “That was instrumental in him turning his life around, being not only a man of faith, but a community leader and an individual that people look up to as a father figure now.”

In their many interviews for the documentary, Perrilliat and Anderson say that some of the words that come up most often in talking about fatherhood are “identity” and “presence.” Young men need present fathers, Perrilliat argues, to help guide and shape their identity. “If they don’t know who they are, someone will give them their identity, and most of the time it’s the streets,” he says.

The men hope that sharing these stories will help others develop a healthy identity and commit to being present for the next generation. “As Scripture said, we overcome by the blood of the lamb and the word of our testimony. The word of our testimony, I believe, helps other people to overcome,” explains Anderson. “What we’re trying to do is help them have this healthy model of who to become and … not develop a toxic form of masculinity, but a healthy form that is productive and creative and innovative in their communities and their families.”

This theme runs through all of Perrilliat’s endeavors. When he describes what motivates him, the force of his passion is palpable—and the gaping need he evokes is heart-wrenching:

“There’s a young Black kid walking to school every day that has to fight through five or six different gangs,” Perrilliat says, describing childhood in an inner-city world he knows intimately. “He’s seen his mother before he went to school with a needle in her arm, or beat up by her boyfriend and her eye’s swollen. He doesn’t have any food in his refrigerator, and he’s trying to figure out how he’s going to eat. He’s seeing prostitution and he’s seeing all kind of ways to make money, but he finally makes it to school. But he’s late, and he’s consistently late, and they kick him out of school because he’s late, and then they say, ‘Why can’t he be like other children?’”

Perhaps it is this deep empathy that helps Perrilliat get through to the men who come into his programs.

“When Stewart conducts these sessions, the young men are able to have a light shined on their own lives and say, ‘I did make a poor decision,’” reflects Anderson, “or … ‘even though I didn’t have a good father figure in my life, whatever was lacking in my life, I can become that in my children’s lives.’”

Driven by this passion, Perrilliat continues, week in and week out, sharing his testimony with men and boys, some of whom may want nothing to do with his program, or who may think it’s 20 years too late for them.

Is it making a difference? “Sometimes just someone talking to you can change your life,” attests a participant named Benjamin who recorded a video testimonial after a Man 2 Man session. “That’s what these [meetings] do for people.”

An older man and father, recently released from jail, says during another session, “I’ve been doing this since January. Now, when my wife says something, I don’t get as mad.”

Learn more about the U of R Graduate School of Theology, home of the San Francisco Theological Seminary.

Editor's Note: This article is an edited version of pieces that ran in SFTS's Chimes magazine.