While it has recently grown in popularity among beer enthusiasts, sour beer is now drawing attention in chemistry research circles as well. Thanks to research from the University of Redlands, brewers might soon be able to better understand the sour beer aging process to control flavor outcomes.

“Scientists are very interested in beer and especially sours because they are such complicated systems,” said U of R Chemistry Professor Teresa Longin, a principal investigator for the study with U of R Professor David Soulsby, who initiated the study two years ago. Redlands students also contributed to the research.

The team recently presented, “How sour beer gets so...sour,” at the American Chemical Society (ACS) Fall 2020 Virtual Meeting & Expo. The research was announced at an ACS press conference (with video, below) and highlighted in Chemistry World magazine, on CNN, and in multiple media sources across the nation.

Beer in progress

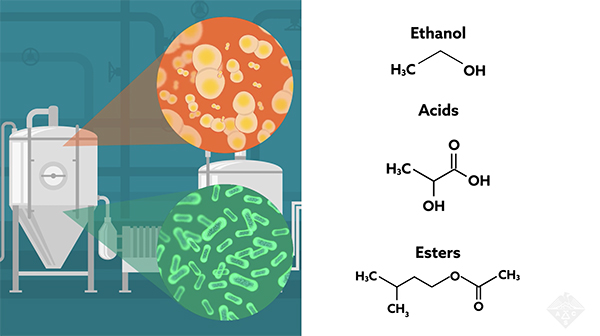

Regular, or non-sour beer, is typically made from water, malted barley, hops, and one strain of yeast — bacteria are always kept out. In contrast, for sour beer, wild yeast and bacteria are both allowed to grow in a brew known as “wort,” which then ferments. The wort is often transferred to wooden barrels, where it matures for months or years. During that time, the microbes produce numerous metabolic products — including ethanol, acids, and esters — that provide much of the unique flavor of sour beers. The barrels themselves can infuse trace components that contribute to the flavor profile.

“There have been several prior studies of the components in finished sour beers,” Longin said. “What makes our study different is that we’ve been able to get samples of beer in progress from many different batches.”

The U of R team partnered with local master brewer Bryan Doty of Sour Cellars to source a series of samples from the same barrels as the beer aged.

Soulsby and research student Alexis Cooper ’20 examined each sample using the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometer — an instrument much like a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine that, instead of looking at parts of the human body, looks at individual molecules to see how they fit together — coupled with a new analysis method for quantitating the data.

“It was my favorite research project while at Redlands,” Cooper said. “The NMR Spectrometer is cool technology. Dr. Soulsby has it set up to be user friendly.”

Ingredients for a flavor profile

They used this approach to track the levels of acetic acid, the main component of vinegar; lactic acid, which gives sourdough bread its distinctive taste; and succinic acid, which is found in broccoli, rhubarb, and meat extracts. They found each acid stabilized at similar concentrations in different batches, although some batches had greater variability.

“These organic acids give sour beers a lot of their flavor, and the balance of organic acids produces very different types of sour beer,” Longin said. “It can be more like balsamic vinegar, which has a sweet/sour flavor, or it can be ‘puckery’ sour. The mix of organic acids is really important for understanding the flavor profile.”

Working with research student Emily Santa Ana ’21, Longin drew on expertise in liquid chromatography/time-of-flight mass spectrometry to search for other compounds that contribute subtly to flavor but are present at levels too low to detect with NMR.

Santa Ana said there is a great amount of trial and error while identifying compounds: “I think what surprised me most was the unpredictability of where certain flavor modifiers were coming from.” She said the research is fulfilling and inspiring and considers working with Soulsby and Longin “a once-in-a-lifetime" opportunity. Santa Ana, now a senior, will continue the research this year. “It brings the textbooks and articles to life.”

“This is a work in progress, but I’m definitely seeing some trace compounds changing over time,” Longin said. “Some compounds, such as tryptophan (an amino acid), start off at high concentrations and then disappear. Others “grow in” over time. They could be additional organic acids, health-promoting antioxidants known as phenolics, or vanillin, which lends a hint of vanilla to beer.”

In the long run, the research will help sour beer brewers. “If a brewer knows a particular combination of yeast and bacteria produces a desirable flavor profile, they can culture more of it,” Longin said. “Or if they know that a beer with a specific combination of acids is especially pleasing, they’ll know when to stop aging the beer, so it doesn’t lose that balance.”

Learn more about studying chemistry at the University of Redlands.