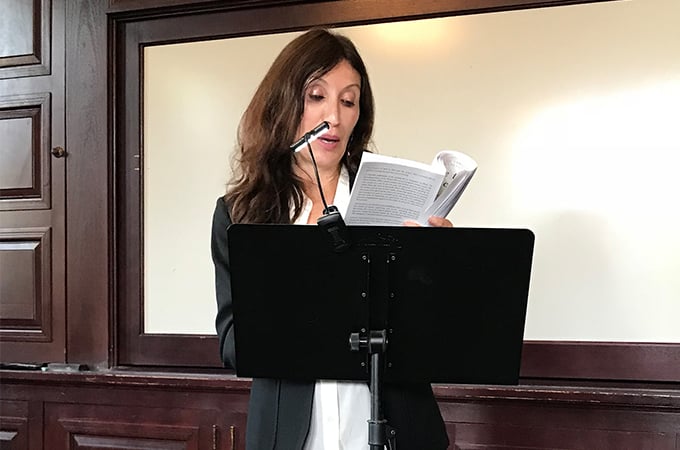

Francesca Lia Block, the author of more than 25 books of fiction, nonfiction, short stories, and poetry, recently paid a visit to the University of Redlands. During her time on campus, she visited a Fiction I class to give a lecture and answer questions, and she also gave a reading in the Hall of Letters Browsing Room.

“I want to take a moment to try to express the versatility of Francesca’s body of work,” said Professor of Creative Writing Leslie Brody during her introduction of Block. “Her books include fairy tales, mythology, adventure stories, heroes, journeys, coming-of-age chronicles, and social commentary. One of her readers, asked to comment for this introduction, told me, ‘Francesca Lia Block is the reigning and original queen of young adult literature.’”

Brody added much of Block’s fiction is also for adults, but whatever the audience, “her books are related in a language that is lyrical and sensible, both ornamental and crystal clear.” The Creative Writing Department recently selected Block for the one-year creative writing visiting professorship. She will be instructing a Fiction Workshop II course this fall and said that she is thrilled to be teaching at the U of R.

Block read from her newest work, a memoir titled The Thorn Necklace, which will be out in May. It was the first time Block had read an excerpt of her new book to an audience. “Usually I write fiction,” she said, “and memoir is a little harder because it’s so personal. So, bear with me.”

Such a disclaimer was unnecessary—Block read about her father’s and, later, her mother’s cancer diagnoses and subsequent passings with a grace that moved many in the room to tears. Looking at ways writing can help process pain, The Thorn Necklace offers insight into healing through the creative process.

Following the reading, Block provided time for questions from faculty and students.

Q: You wrote many works of fiction before you came out with the memoir. My concern as a writer is that once you write the memoir, you lose a lot of your subject matter for the fiction. How do you feel about that?

Block: If you’re familiar with my work, a lot of names of the characters in my books are the names of real people in the memoir, so it’s kind of strange. This book definitely takes me up to this point in my life, but the novel I’m writing now isn’t so dependent on my past experiences. I’m applying certain things in my life, but it’s less autobiographical than some. It feels like there’s always more material. A lot of the stories in the memoir have already been used in the fiction, but they’re novels, so it’s almost in reverse.

Q: After leaving off with Weetzie Bat, I’m curious as to why you went back and whether you’ll ever go back to that world again.

Block: I wrote these books when I was very young, then I moved on and did other things. People certainly had asked me for more of them, but I didn’t really feel it authentically. Sometimes I do write books because it’s an assignment, but I try as much as possible to do it in a more organic way. At that point in my life, I think I was 40, I had a period where I didn’t feel the magic in my life as much, and then it started to come back. And Weetzie just naturally came back, but she’s now 40, when she had been a teenager in the first book. After that, I wrote the prequel, when she is 13. I don’t think I’m going to return to those characters per se, but I’ve said that before.

Q: I’m about to graduate, and I’m thinking a lot about my writing process and how to fit that into the shape of my life. What is your process? Do you dedicate time to sit down to write or is it something that just happens?

Block: When you’re starting out, I think it’s important to have a very regular schedule. I don’t have one at this point because I can’t, as I’m doing a lot of different things and raising kids. Now, I look forward to that part of the day—when I can write. I can put it off, and I know it’ll get done because I love to do it. But I still recommend that you create some kind of schedule where you devote a certain amount of time per day. And it doesn’t have to be slogging through a novel when you don’t feel that inspiration. It can be doing other kinds of exercises like writing poetry or reading specific books that inspire you. There are a lot of ways to stay connected to it. And throughout the day, I’m thinking about my book; it’s not too far from my mind.

Q: When you write a novel, do you write it in order, or do you write by scenes?

Block: I jump around. I generally move in a direct trajectory, but there will be times when I’ll write the end scene earlier. Or I’ll write certain scenes and realize that they don’t go there. But I do try to think in terms of highly impactful conflict-laden scenes between the characters. I’ve also started to outline; I didn’t used to when I had more time to write, and I would meander and let my psyche create what it wanted to. Now I’m under more pressure with deadlines. I like to teach outlining to my students, but I also think there’s something to be said for that free writing as long as you have a general idea of where you’re going and think about writing in scenes. A little way into the process of writing a novel, I generally know where it’s going. [For] the novel I’m writing now, I’m on page 220, and at about page 100, I wrote the last scene. It’s something to work toward, but it might change.

Q: What you read were memories, and in the trajectory of your writing, you transform those into fiction. I wonder if you felt that was almost necessary to understand them in some way—like you had to move them out of reality into some other place.

Block: I had never wanted to [write] memoir before now, later in my life, because when I tried before, it would fall flat. There was something about fiction that distanced it just enough so I could gain perspective. Now it was so long ago; my dad died when I was so young. I had a lot of time to gain perspective through writing fiction. Whether or not you’re using magical realism or fantasy or you’re reshaping it for the purposes of the arc, I think fiction allows for some of that distance I like and need. At the same time, it’s exciting to try [a memoir]. I think by nature I’m more of a fiction writer, probably for that reason, although real experiences underlie the fiction I write. I do think the distance from the raw emotion is the healing aspect of it. It’s not just writing it down; it’s shaping it and forming it and making it art.

Q: Where can we find out about the 12 questions for structuring a novel, and which is the most important?

Block: The 12 questions are in this book. I think the most important ones for me are about the character. They are: What does the character want? What does the character need? What is the character’s gift? What is the character’s flaw? What is the character arc? If you outline a story using these questions, it can be effective, but I think it’s better if you pour out your story, at least a little, and then go back and think about these questions. Otherwise, it can be a little stifling. How can you really know until you have written some? I recommend that you use the questions, but also that you explore intuitively what the story needs.

Q: Has there been in your life a piece of advice or a specific book or piece of art that has transformed your approach to writing?

Block: I think the advice to keep writing is the most important thing; don’t give up. I have projects I’ve been working on for 30 years. I’m like a bull; I don’t stop. I think you have to be really devoted, keep working, not give up, and not listen to the critical voices we all have. So many works of art have inspired me. For The Thorn Necklace, I used the Frida Kahlo painting because of what it represents about pain and art. There have been so many writers and so many images, and music—I remember going to hear music when I was really young and thinking, “I want my fiction to make people feel that”—crying, sweating, shaking, emotional. How can you make prose to that? I don’t know if you can; I’m still trying.

Q: What’s your least favorite part of the writing process? Or the part that you find most challenging?

Block: A lot of what The Thorn Necklace is about … For me, writing isn’t that hard, but life is really hard. So, what I try to do in this book is say, “O.K., I’m going to look to my writing to see how to live my life better.” For the writing part, of course, there are times I’ve felt discouraged—I’ve cried; I’m not immune to it. But, generally, I get back up and keep going. For most people I talk to, [the problem is] the self-doubt: “Is this any good? Are people going to read it? Will it get published?” I certainly have that myself. I’m pretty good at ignoring it when it comes to my writing. [It helps to] say, “While I’m doing this project, it’s like a baby. I’m going to be really gentle. I’m going to write what I need to write and get it all out.” Then, later, you can put the critical hat on. Separating out the judgment until later on in the process is important. Never be super harsh, just be honest. As this book starts, my dad told me when I was 19, “You are a writer.” He yelled it at me over the phone in the dorm room while he was very sick. And it got into my subconscious. It helped me. So, what I’m trying to do here is go, “You are a writer.” If you have that desire to write, that means you are a writer. You just have to keep going.

Q: In graduate school, I took a young adult literature course, and my professor talked about how impactful Weetzie Bat was when it first came out [with] a non-tragic gay character. I was wondering if you could talk about where you think young adult literature is at with LGBTQ trends today.

Block: I know it has changed a lot and there’s a lot more. I think the direction it has gone in is great. For me, when I wrote [Weetzie Bat], I wasn’t trying to make a statement; I was like, “I love my friends, I love my brother, I’m just going to write about the people I love and the way I see them, which is not tragic.” I’m in love with them. They’re beautiful. That’s the whole book: a celebration of people.

Q: How did you first get published?

Block: I’ll tell you how I did it, and then I’ll tell you how it is now, which is, unfortunately, very different. When I got published, I had recently graduated from college, and I sent my manuscript to a friend. She gave it to a friend. They called me up and said, “We’re going to publish your book. We’ll give you $4,000.” I started crying with joy. I didn’t know who was publishing it; I didn’t know anything except I was so happy. I hadn’t written it as a young adult book, but it was a young adult publisher. And then I continued to publish with them. Then I got an agent, then I kept publishing. It went up and down, sometimes good years, sometimes not, but I kept doing it. I’ve been very lucky.

Now, you need to get an agent; nothing happens without an agent. Even if I gave a student or friend’s manuscript to my publisher, they would want it to come through an agent. In terms of an agent; it’s all about finding a person who gets you. I recommend going to writers’ conferences, just meeting as many people as you can. Look up the people who represent the writers you love and write to them if they accept queries; say how you genuinely feel about a client they represent. I can tell if someone sends me a fan letter and they really are a fan versus they want a favor—which is fine. I can tell the difference. An agent will be able to tell. If you write, “This book changed my life. I read it when I was this age—” whatever genuine thing you have to say, you can make that connection to the agent. A lot of them will accept queries and submissions, and some won’t. If you have any kind of personal relationship with an agent, put all your attention into that one. In my opinion, I wouldn’t shoot for someone else. If somebody is caring about your book and has an emotional connection to it, that’s the person I would pick. From there, they’ll maybe give you notes. And then they’ll talk to you about submissions, and you’ll go forward from there. These days, it’s all about the agent and having that really polished manuscript that’s ready. It doesn’t have to be perfect, because what’s perfect? But you want it to be as polished as possible.

And if we expect people to buy our books, we really need to support each other as writers. Build that community; it shouldn’t be a competitive thing. We should be lifting each other up.

Q: I think a lot of the time fiction writers write based off of their lives. Have you ever had trouble with material being too close to your life—especially worrying that people would know who it was about?

Block: I think that’s more of an issue with memoir than with fiction. With fiction, I do change things, and I’ve never had an issue. Sometimes I will be a little concerned with something, but I’ll try to change it just enough. But these are our experiences, and we get to own them, and we get to write about them. You can change certain details, but it’s your story to tell. I’ve also heard some people say, “Well, I don’t want to hurt people with my writing.” And that’s a choice, too. But I wouldn’t want it to inhibit your process or self-expression. You can always get it all out, totally honestly, and then step back and make some choices about that. For memoir, it is going to be a little more of a challenge in that way, but again, you can change details; you can change names. And it is your story. We have to tell our stories. I think it’s essential for our well-being and for the world, really.

For more information on Block and her work, see Block’s website. For more on U of R’s creative writing program, see the Creative Writing Department.